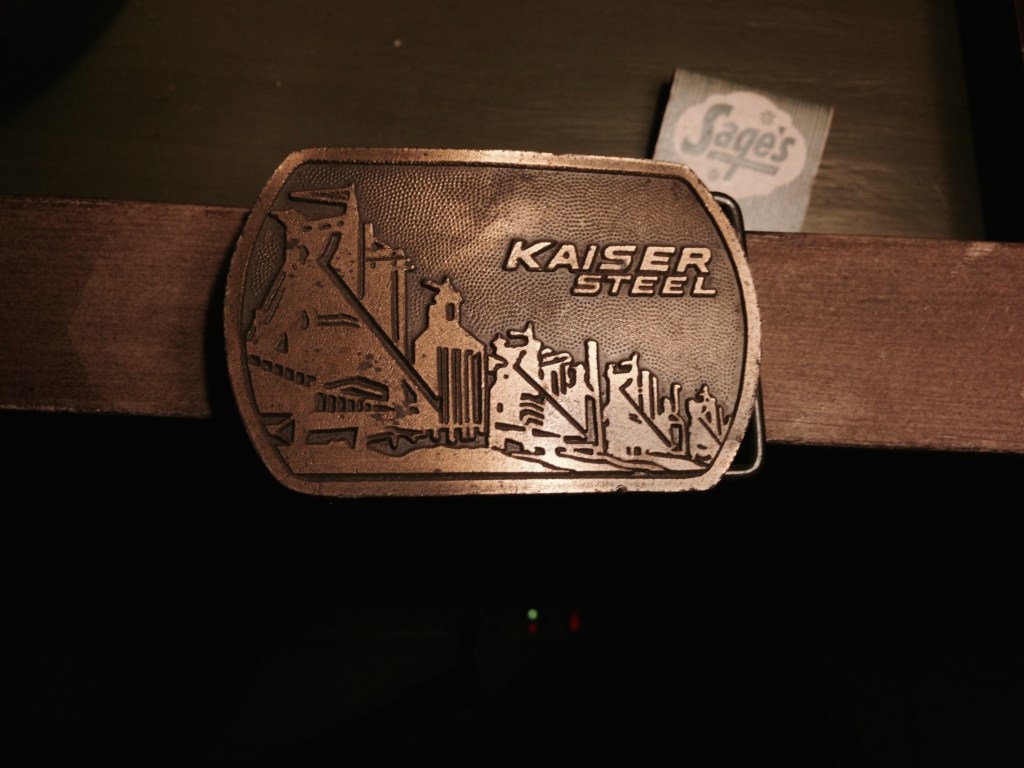

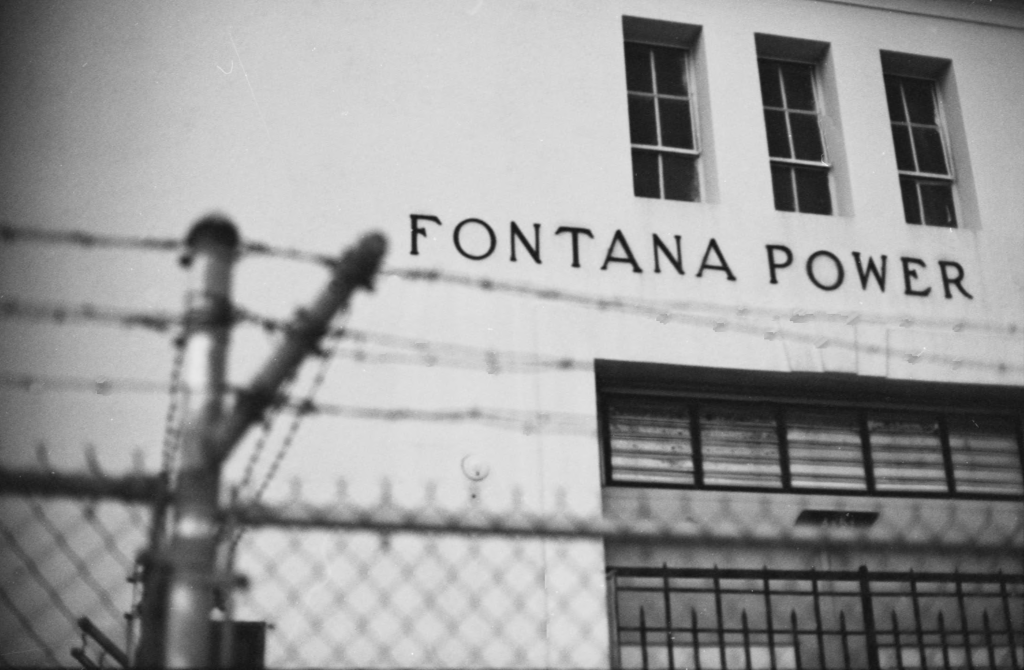

Find here notes for a talk I intended to share regarding the new Bamboo Dart Press release, in chapbook form, of my short story, The Coin Cold Heart. It’s a story that is told as if the imagination had its own imagination, and it regards my home caliche, the town of Fontana, California. It’s an example of just how far in telling I will go to assure the world that I’m not a historian. It reminds me of the time my good friend Ben Harper contacted me about his bringing David Lynch and Laura Dern out to our house in Upland, California to talk with me about the dust of our region. Lynch was woodshedding ideas about a movie to be titled Inland Empire. So far all he had was the title. I wanted to just tell him that I’m not an authority on anything, and close to proud of it, but I couldn’t resist the chance to meet Lynch, so I agreed. Well, the plans were made, and the day came, and because it’s my life, they were deluged by a rainstorm on Holt Blvd and then forced to retreat. Close but no cigar. But it did get me thinking of what a good idea it seemed, so I went out that week and took a series of photographs of Fontana to submit for location fodder. The Fontana Boxing Club, The Iron Skillet (Ontario), as well as a healthy collection of decrepit alley ways, every run-down bar and every vestigial church to match it. As it turns out, I like to think that it was my agoraphobic bumpkin contribution that inspired them, in the long run, to film the entire movie in Poland. To quote my own self, “It’s the thought that almost counts”.

(photo: Patrick Brayer)

(Excerpt from The Coin Cold Heart)

That’s what sunglasses achieve. They take us back to the vision we peripherally remember from underwater, a time before we evaporated that tell-tale dimension and parked our gills at the curbside for a wiggle onto terra firma. Arriving at the present, greased beyond our grasping, in that million-year vehicle that we call, “our today”. We are brave enough to harken it, but we are stupid to ever think it might come when we call. Notice how when you go to jump into the ocean, treadmill waves like a roll of nickels perpetually try to muscle us back onto the earth, linebacker fashion, cast from its garden of brine. To each his own, say the elements, but to themselves only. For what to one person is a comically painted sunset, a rendered attack of yellows by some blue-haired art-club grange-hall bitty, was to another an acetylene gold ray raining down upon a sparsely attended graveside. No one is alone in the casket, every person is buried with their shadows.

(Photo: Patrick Brayer)

I began working on two collections of short stories, thirty long years past, as a sort of palate cleanser for my songwriting pursuits. One set I called The Pomona Sorrows, and the other, The Fonta Files (a nod to The Rockford Files, and the gang slang terminology for my hometown of Fontana, California). I didn’t cotton to my being a historical expert of any kind, I rather reveled in the poetical mythological license I would wield, as if it were regional paint peeling, adulterating and filleting the crown rich memories of a blue-collar shanty. In a mirror I don’t look like any writer I’ve ever heard of, in the light of a dim bulb, with a secondhand physique my reflection barley looked back. A frost-bitten Micky’s Big Mouth malt liquor gives my day and its cock’s-crow what personality it can. I sport a mud-colored t-shirt, two sizes too tender, that confesses that I’m in fact “Powered by Frijoles”, a humorous attempt that I’m amiss to live up to, which is excusable because I woke up in the shirt, only slightly remembering a time when the slogan was funny. Closing out the haberdashery of my statement are some apostle-like footwear and a pair of overzealous cargo shorts that have pockets I’ve never used on this side of the Costa Mesa Dixen Line.

(Photo: Patrick Brayer)

At first glance I thought that songwriting and short story scribbling could be seen as one and the very same. But I’ve come to realize that they are night and day, maybe brothers from a different father’s mother. Songwriting is like giving birth. Which is true, albeit it sounding more like something your grandma might say in the shade of a magnolia, tracking in mud from the truck garden. Out of my control I deal with it when it comes out of me, before the swaddling cloth. I let it be what it wants to be, while on the other hand, a prose story, is created inside of me, a ship in a bottle, that begs to be relentlessly combed over hundreds of passes until I throw my hands up and curse infinity. I can’t say for sure, but The Coin rather looks like it was inspired by my emersion into the mind space of Italian novelist, Italo Calvino. What I’ve learned over the years was to just finish your thoughts before you start second guessing the work. When I write I go into sort of a trance, for the lack of a better word, a trance state that must convince me that I’m writing with the masterpiecian powers of such as Calvino. Later, when my ego sobers up, I realize that I’m nowhere near Italo, embarrassingly so. If everything works as it should, before I try to find bullets for a gun, I look and see that my failure is a unique voice beyond its own control, an originality that I didn’t sign up for. I rarely take my own advice, but I often suggest to others, “rather than being something you’re not, take your weakness and make it your strength”. During the pandemic, besides the death and destruction, I was in heaven. My wife took over my recording studio (this is not the heaven part) to teach English Literature, and I moved into the house to attempt to unearth and bring back to life these practically Sanskrit writings from three decades afore. I then set out to read in exercise all of Nabokov, Faulkner, Raymond Chandler, and Charlie Wiliam’s (the Mangel series), not to mention devouring Moby Dick (the greatest doorstop ever written), following that with Heart of Darkness, and Don Quixote. I was spinning in masterful sentences, and accepting their impossible benchmark, setting it upon myself not to concentrate on the hard polished genius but rather the overall essence. That’s the only part that can’t be stollen. Making it sacred. Whether I learned a lesson here cannot be the point. The point is that its achievement is not in any sort of goal oriented final enlightenment, but more in the liberating power of the search, a searching that has no author.

(Photo: Hollace Brayer)

(Excerpt from The Coin Cold Heart)

At one time all the people of Fontana lived on self-fashioned boats or barges, for this was a prehistoric period in which the world was all water, and dry earth had not yet been invented, nor mountains pushed up into eruption, yet to meet their carnal destiny with the cobalt vestment slashing shadows of the future. Scientists of today have come to discover the fallacy within the long-adored Big Bang theoretics, its galaxy turning to a floating congregation of globes, only to find that the San Gabriel Mountains were, in anthropological terms, no more than a muddy bootprint left behind by a giant, step-stoning from planet to planet on its trek across the universe. It was later known to have been distracted by a meteor, tripping on Jupiter, and banging its shin like a bloody sunset on the sharp corner of a black hole.

All artists of all mediums have one thing in common, a never-concluding interest in the human condition. I once wrote a song called Note to Self to Say Goodbye, that started,

“The moon was drawn and quartered, and there on its back, and rightly symbolizes a champagne that’s gone flat”.

Only seconds into the song and I’ve already pulled the moon from the sky and chopped it up before you like a Black Dahlia investigation. That’s what the power of the imagination can do, so why not use it. In The Coin I take you back to Fontana in pre-historic times when life was just then crawling out of the ocean. The part about Woody and Lena’s Good Time Shop was true to life. He really did play me a reel to real recording of Johnny Reb, a shocking racist spoof that left me stunned. It left one with the darkened sensation of not knowing what to do with such information, and challenged you as to your original interest in the voodoo aspects of the human condition in the first place.

(Photo: Patrick Brayer)

(Excerpt from The Coin Cold Heart)

I checked the revolver; it was loaded all the way around. I tip-toed into the living room and without ceremony shot Sin Coalfield four times in the back and he fell like a sack of turnips, just as a dead man’s supposed to. His trucker-style ball cap tumbled across the floor as if blown by a ghost, reading ‘Pomona Feed’ on its skulled bonnet. I would ordinarily think that that was a clue or an omen, but I was beyond all that now. I then realized for the very first time that transcending and giving up are identical twins, although, as the rules go, one of them must still choose who plays the black sheep in the family. I gathered up the teakwood guitar and amplifier and made a few lumbering trips loading them into the coalmine darkness of my Ford Fiesta, the scene outside lit just barely by the bone saw teeth of the moon. I came back into the house and sat and cried in a widow’s moan until sunrise, with Coalfield at my stocking feet, with the blank expression of an egg, in his bathrobe and kilt, in sort of a nautilus shape, looking, in the same manner, both absurd and regal simultaneously. The doomed nature of the scene reminded me of a story my uncle once told me regarding the true history of Saint Patrick. It seems that when he was driving all the snakes out of Ireland each one in exit got placed a potato on its back, thus putting the famous famine in gear. Outside the weather changed to hard sheets of rain, jostling the trees into the shape and surrender of desperately blind bodies clumsily dressing in the dark.

(photo: Patrick Brayer)

I was once cornered by a kid backstage at The Bottom Line in New York City who informed me, regarding my Fontana songs, that his friends and himself were planning to move to Fontana. Having never even considered that possibility, I told him he was getting it all wrong, and that I was just trying to get others to at least consider the corrido-Steinbeckian-charm of their own hometown, and surely not to transport themselves to the burial ground of my own personal dolled-up disappointment. Before I scampered back to my steel town digs I agreed to meet him for coffee the next day. Fast Folk Magazine had recorded me that night at The Bottom Line which would eventually find itself, to my surprise, of its own volition, put out by The Smithsonian Institute in a collection that also included Dave Van Ronk, Suzanne Vega, and Shawn Colvin. It was one of those selfsame songs I wrote about Fontana, called Funeral Town. The next day he probed me further, being young and almost carrying a skateboard, questioning “how do I dream up this stuff?”. The double expresso I was having was almost just as guilty as I was for my answer in parting. “If you can tell me where your dreams come from, I will then tell you where my songs come from”. In other words, it is in the art of lucid dreaming that comes forth a formally clueless bard.

(photo: Patrick Brayer)

A shout out to two maestros of publishing, Dennis Callaci and Mark Givens of Bamboo Dart Press for giving underdog exposure to a catalog of local writers. I don’t flutter in the business world with any noticeable success or acumen. In, at one point, looking for a periodical to submit my writing to, all I could come up with, that looked interesting, was Modern Drunkard Magazine. I sent them a story from my Pomona Sorrows collection; one called The Bloody Mary Mountain Boys. It was about a bluegrass band that formed in prison that took Shakespearian turns. I felt it had everything an alcoholic could dream for. But alas it wasn’t accepted and didn’t even merit a rejection slip. In response I did what I’m best at, I gave up, went back to writing for my original inner audience, motley and malnourished as they might be. I wanted to give up on them also, but how could I, they were already in the starting gate.

Hey, Patrick. Always good to hear from you. Patrick and I have been talking for a whi

LikeLike