(photo: Patrick Brayer)

As a storyteller, the hardest thing to do is to imagine beginning at the severed end of a life. When someone dies, we each go our own individual way together in a low flying trance. Not in a static saunter but rather in a rhythmic march through our own version and cadence, clocked through a rusty red claymation. Me, for myself, I questioned if Roy Hyde were not, after all this, just a personal dream, with a capital “D”. Too good and salty to be true, with a sickle smile as if something were constantly up his sleeve behind his eyes. The beekeeper, the Wizard of Oz sawmill owner and operator, capable of rooting the truffle out of any situation and sanding it until it’s his own. Peafowls in the side yard crying out as if in Flannery O’Connor’s voice stark in her wallflower anguish, at being long most barren. For ultimately it is agreed upon that the peacock’s sound is the sonic signature of full-cry loneliness.

The very first time I laid eyes on Roy Hyde historically was in 1997 while he was hired to put in a road to snake up to a creek house in south Alabama. We eyed each other north to comparative south in evaluation, a task in itself due to the squinting sun, and shrugging in our apposing perspectives. He wore a mercurial patterned tie-dye t-shirt, sporting a forgotten hula skirt of scraggly hair the shade and timber of a wooden nickel. He was a hard worker and you just knew he had history tucked away somewhere in the hardscrabble viny woods of Arkansas and perhaps Birmingham. Me, in diametric opposition, hailed from Southern California where whilst living on an egg ranch with no surf boards my dad ran a steel town donut shop. Roy concluded in his mind immediately that I would be on the farthest edge of worthless on his road gang. “Don’t show anybody that you can do back breaking work if you don’t want to end up in such”, seemed to be my motto.

A week later I performed a house concert in Fairhope Alabama. I was flown out originally to help promote a recording of an old friend Eric Schiller, called Leaf of Absence. In my decision to take on such a frightening trek, I talked myself into doing so beyond the reaches of my agoraphobic nature. I would go as a journalist, I told my gullible self, delve into the source history of racism, maybe attend a snake handling trance-church or two. Boy, was I disappointed on that front. Imagine my chagrin when all I got was a bunch of kind and thoughtful people living in a single tax colony. I met Roy the night of that concert, but he just stood there like a hardened church mouse, sussing up the situation, wearing a leather jacket over the same aforementioned tie dye shirt, calling it now, evening attire. On a cassette I made of that performance I noticed that I called it: Live from Eric’s Velvet Lung, which did no better than to just remind you of my slipping mindset. A week later Roy arrived at the place I was holed up in and handed me a stomp board he had fashioned for me from his sacred stash of Cherry and Walnut lumber. He commented on the piece of plywood I was previously using to keep the rhythm to my songs: He spouted, “That just won’t do!”, and he likened it to kneeling at a kudzu cross.

He had already heard my music, and when I saw that stomp board, we instantly recognized each other as what the other was always looking for, a missing piece of brotherhood artistically, and into a wealth of even deeper indescribable reasons. Roy was a world class person, humble yet animated, not to mention a world class woodsmith. I christened him as The King of the Wood Imaganeers. You could look into one of his furniture pieces and be reassured of a depth beyond believing, and an even more far-reaching dimension. It was like examining the iris of a God. Thanks to him I began to try to look at, or at least consider my own works on that very level. We spoke often of such things, which to sidestep sounding self-flattering, we kept just between ourselves, close to the vest.

There were many tales of his early exploits, such as meeting Willie Nelson in the early 70’s, involving the lore of marijuana and turquoise smuggling. About them walking into a room together through opposing doors, like two golden hearted gunslingers, looking identical and shocking even themselves in a funhouse manner. He attended the tail end of the Selma Civil Rights March with Martin Luther King, a display for which he was railroaded out of the town in which he lived and taught, which inspired him to then take up a job as the only white instructor in an all-black school in Prichard Alabama.

This was all before he met the love of his life, his Lithuanian bride, Allie, who was his Ginger Rodgers, doing everything he did quietly and backwards in high heels. They purchased a chunk of wooded property and had a one-story house moved there in pieces which they then rejoined, building a high spire betwixt the two pieces, thus make an ‘eighth wonder of the world’ caliber haven, what I like to call, The Hyde’s Wooden Cathedral. Another thing worth adding is that their philosophy concerning woodworking was one wherein they wouldn’t work with any lumber that came from a tree that didn’t fall of its own accord. They sawed no trees down in the making of their movie.

One time when I was preparing to do an impromptu concert in their farm kitchen I cornered our 14 year old daughter in what I considered a life lesson. I told her to watch Roy’s eyes and body closely as I played and take in the sight of someone who knows how to listen with his soul. I was humbled when I felt that he could listen better than I could play. I never knew until I played for Roy that others, even though present, weren’t quite in attendance. It reminded me that I wasn’t crazy when I stepped away from a life of stage performance. I just couldn’t believe that they were listening. It’s not their fault of course, but it’s still true.

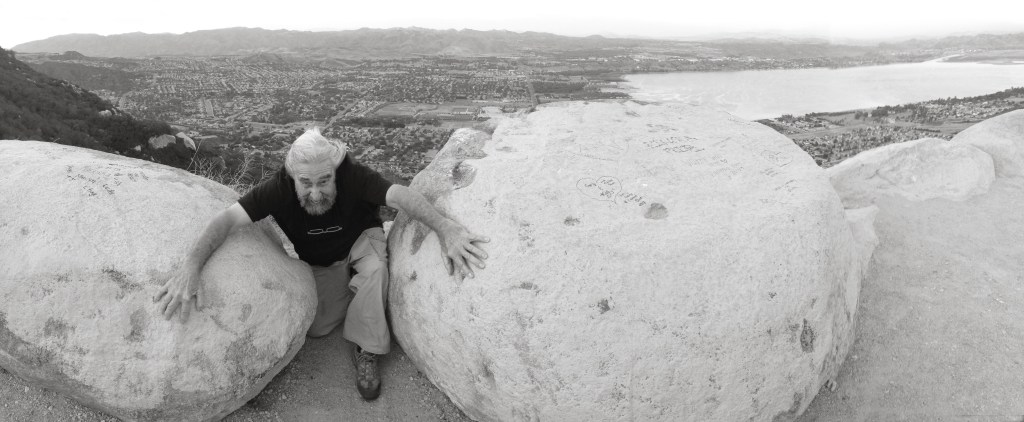

(Here’s Roy Hyde acting out the entire Old Testament in Elsinore California: photo Patrick Brayer)

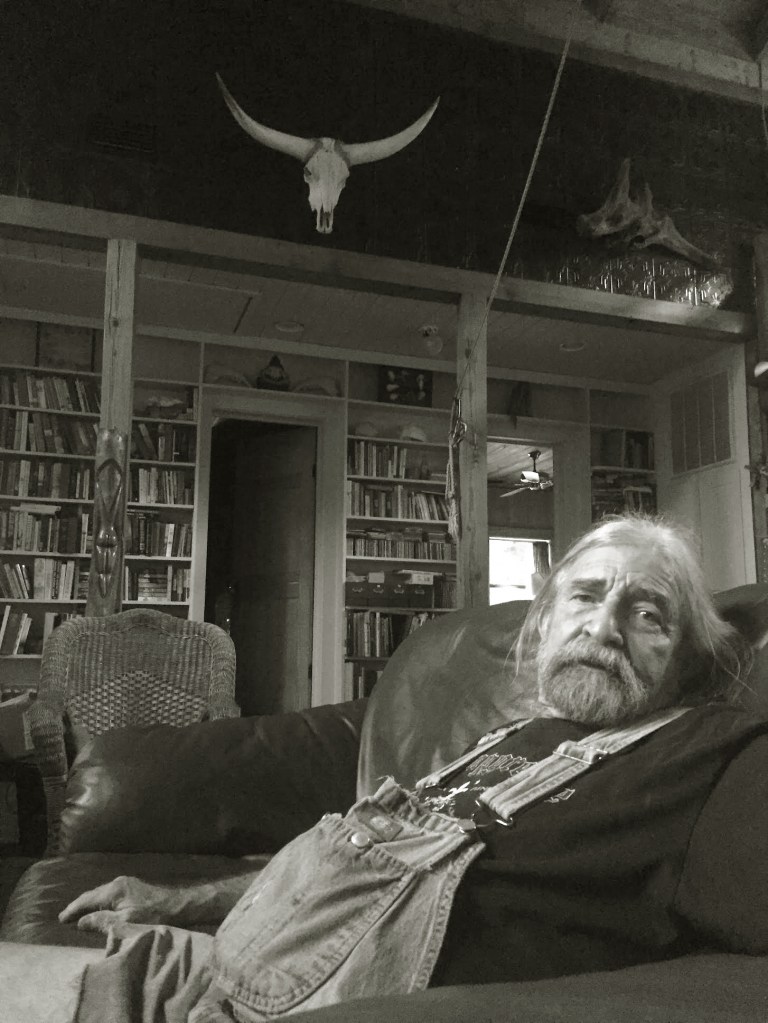

Then there was a time, some thirty years later, when his hair turned from wooden nickel to trail a ponytail of feathered alloy, that we bonded over a similar love of literature, both citing that our favorite book of all time was Cormac McCarthy’s novel Suttree. The last time I saw His-Royness in the flesh, Christmas of 2024, I gave him a 1957 copy of another one of my favorite southern scribes, Andrew Lytle, a book called The Velvet Horn. It was at his bedside when I walked out for what was, it turned out, to be our last visit. I imagine that it was still there when he decided that he had better places to be, and that now it was time for the peace that was well earned by a life lived as colorful and kaleidoscopically-hopeful as a hippy lightshow.

Posing in one of his many earthly incarnations Roy, regal and deacon-like, decked out in a neglected suit, in the spring of 1999 joined my wife and I in holy matrimony beside a cottonfield in Daphne Alabama “By the powers vested in me and Rolling Stone Magazine” he would tell you.

I wrote a song upon first meeting everybody and dedicated it to both him and my wife, a psychedelic ballad called The Invisible Mark. It contained a line that he remembered from a fellow prisoner in the House of Corrections, “I’m walking in chains and flying in my dreams”. In another, Bar Owner’s Daughter, I quoted him with “Don’t make me raise my guidelines.”

Don’t make me raise my guidelines

Don’t make me venerate.

Barstools full of ex’s she tried to incinerate.

But now her eyes turn to candy on the vine.

The Hyde’s were infamous for their New Year’s Eve burn-piles at which couples were known to arrive as friends and after an evening of inebriated ritual, “Salem Style”, wake up in the dirt of dawn as lovers, like potatoes cooked in cinders. It apparently was also used to clean the yard of fallen debris if one were searching for a practical sense, which seemed to slip all minds.

(photo: Patrick Brayer)

One day, in fatherly fashion, to a Mormon Tabernacle of frog’s chorus and prairie chicken’s choking on the humidity, he taught me the fine art in how to properly skunk a beer in the sun, and then made me several fish-throat tacos, made from fisherman’s salvage on the docs, grilled out in the yard upon our taking a smoke break from a self-inflicted marathon of W.C Fields black and whites, which Roy took as serious, scratching the tumbleweed of his biblical beard. Then he brought me out a plate of cantaloupe, which though it appeared as mortal, was the best I had ever eaten, leaving me thinking, “This guy’s onto something”. Leaving me ultimately with the obvious conclusion: “If I wasn’t busy being me I’d wanna to be this guy”. This left me in mind of an old Harlan Howard song The Wall which spouted in a prisoner of life’s lament: “Many have tried and so many have died, but they never made that wall, no they never made that wall”.

The very last time I talked to Roy Hyde we were on the same page, the static of the telephone like a soft jet engine, time ticking like the heartbeat of an orphan tapping on a barn door, both of us agreeing that if dying was going to be this much work, that we perhaps might just as well not bother.

The Invisible Mark

There’s a bachelor awakening / with a pocket full of swizzle sticks

Her gray wool coat hair pulled back / and a heart of rosy bricks

Like crayons and star fish / melting on the beach

Over black and white TV set / for her I begin to reach

Lurching before January flowers / in the square foot slow of molasses

Plastic magnolias blossoming / in her costly sunglasses

That’s why I’m walking in chains / and flying in my dreams

Look how perfect the body / that has no seams

My hands turn to gloves / playing the fiddle they turn to doves

But against her jaw in the dark / I draw an invisible mark

Like jello moves through razor wire / I will dream of a fire

And at least warm the chains / as we fly a little higher

Each link is a link as freedom / each a feather in black

Each one the difference between / holding and holding back

I hope you won’t notice / as I come into view

In public tranquility / I walk in chains to you

—–

World aching harmonies / to a flailing of heart beats

Sounding black walnut under the foot / tossing jewelry into the sheets

Pork baked in apples / and an Everclear mao-tai

Fortune has a plywood center / salt and radishes will make you cry

Fire wouldn’t even know what to do / it couldn’t even light the face of a clown

If you didn’t hold out a bright hand on a golden road / for it to wrap around

—–

When I walk away from you / I feel I mispronounce passion

And I can’t help but feel / I walk away from all form and fashion

But let’s never forget / that the parents from which the rose is born

Are ever hard at work / being the parents of the thorn

We sometimes live our whole lives through / and when it’s done

We realize that the rhythm was always / waiting patient inside the drum

Written by : Patrick Brayer

2-17-97 Alabama (for Roy Hyde and Holle McKnight)

Here are some autobiographical notes written by the man himself:

“I grew up on the outskirts of Birmingham. The Japanese surrendered on my 5th birthday. I had a Tom Sawyer childhood. I taught Wilt Chamberlain how to do a yoga headstand, I was at the King March in D.C. and lived off the land in a teepee in a commune in Arkansas. I am also licensed and can marry people. It has been quite a life and I never thought I would get this old. I am a cancer survivor and have had several surgeries. Physically I am a mess but I feel like I am 18 years old.

My father died when I was 18 and I got into college on a bet in a poker game. I barely got out of high school with a D minus average and went to Alabama College, which is now the University of Montevallo. The school was going broke and they had to take in men for the first time and I was in the first class that had men. It was 14-to-1 women to men so our odds were pretty good.

I was a redneck and had read only a couple of books until I went to college, then I got interested in religion and philosophy and Plato. I was exposed to so much and I loved it all. I went to Tuskegee and met up with a group of black students and ate dinner and talked. That changed me. I was in Montgomery for the end of the Selma march and saw the big show with Peter, Paul and Mary, they were my heroes. I was stupid and bragging about singing protest songs and people got after me when I got back to Birmingham and I lost my teaching job.

After Sputnik, there was a lot of money in science and they paid me to get a masters degree in the teaching field. Instead of going to graduation, I went to Woodstock and didn’t come back. I have a couple of masters degrees, one was in radiation hygiene which was nuclear safety. I taught science for several years. For a while, I was the first and only white teacher at Blount High School.

When I was a kid, my father came home with weird stuff. We raised rabbits and quail and parakeets. One time he came home with a pool table from the pool hall. He also came home with a print shop and we had a whole print shop in our basement. He had a jigsaw and we made Christmas decorations out of plywood that we hung on top of the house. I got interested in building things.

When I was living in Arkansas, there were some persimmon and black walnut trees and I had a jointer. When the limbs fell off the trees, I played with them and whittled them down. The thought of getting a sawmill turned me on. I appreciate the tree and what you can do with it. I have been thinking about teaching a class to help other people learn how to make things out of wood. I am not as strong as I used to be and I have to trick people into helping me.

These are from a tree in Daphne and will turn into coffee tables. That board is beautiful, it is a piece of red oak and a special sawing technique brought the flecks out. One of the tree services lets me know about the trees and wood they find. A lot of the high-end builders let me know, too. Cherry is my favorite, but I like them all. Black walnut and magnolia are a lot of fun and I make benches, tables, and beds. I try to use all pieces of a tree. I love the feel of smooth wood. When it is right, God it feels so good.”

I have now read this beginning to end three times. George and I are still grieving as Roy died two days to the hour after my 96 yr old mother. I was holding her hand. George was called to Roy’s side by Allie moments before he took his final labored breaths and they were able to speak of the love they shared for going on 60 years best friends. Our lives seem hazy this year without those two who we were accustomed to being with most days. We visit Allie together from time to time but George goes over regularly. I would say she is now his closest human, next to me of course. She will be taking him next month for his MRI as I have patients all day. George is really not the same since Roy died and the doctors want to see what is happening inside his skull. I think part of him departed with Roy. I wonder how that will show itself.

LikeLike