“Family souls whose coal mine brains were scarred from hard soot, and the easy handling of weapons”

(Carla Coldiron Mcgill)

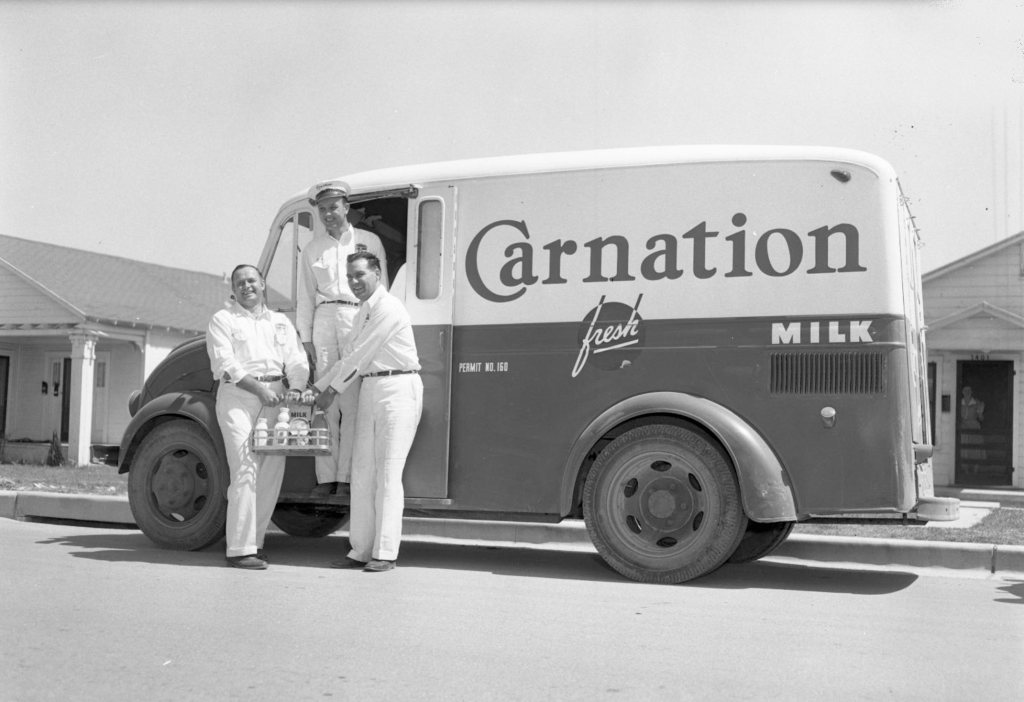

What makes this an American story is the fact that it can be told as a history of a string of vehicles. In my mind, there is a metaphoric junkyard dead-grass cemetery that splays out all our vehicular histories, Nash Ramblers, metallic Buick coupes parked, seemingly obedient, holstered in its own parking slot, before clap trap apartment complexes, Caprice Classics, and the crown jewel, my father’s Carnation milk truck. Once while on his dairy route he traded his Army luger to a housewife in a floral caftan for a honey-colored Spanish guitar, which was, unbeknownst to me, to start me on my own particular path of rejection, and its black sheep half-brother, poverty. Whenever I remember back to that rusted and retired Carnation milk wagon I always just see the word ‘reincarnation’ instead. It foretold of my predestination as a 1970s-caliber headshop hippie. But it always got me thinking of the possibility of a cosmic return. But in my imagination, I never thought I would come back to earth as a turnip, or a bluebottle fly, let alone a celebrated astronaut who had eventually fallen from grace, rattling some bushes with a teenage beauty queen. Nor would I have ever thought why any of my words might live on, hugged from the sweet hereafter in parentheses.

(Stater Joes)

I awoke from one of the many recurring dreams I had wherein I found myself reincarnated as a paper bag, more specifically and vividly a Stater Bros. shopping sack, blown up in dance against a cyclone fence on an eternally windy day. I would actually wake up with grit in my teeth and the checkered marks of the cyclone fence on my cheek. Even though I know that the paper sack is just a conjured thought, I still imagine, whenever I write a poem, that I am scrawling on that bag, and that the paper cut that ensues is real, and that at one time my blood was paisley. As peculiar as these clues all sound I still couldn’t find myself believing in the phenomenon of belief, so I just let it ride. My father used to say of death: “It was good enough for my parents, it should be good enough for me”. I being useless and hiding in the shell of my poetry could only see death as some India ink spilled on the horizon from whence a murder of crows banged rapidfire, ptang ptang, against your mind, lights out.

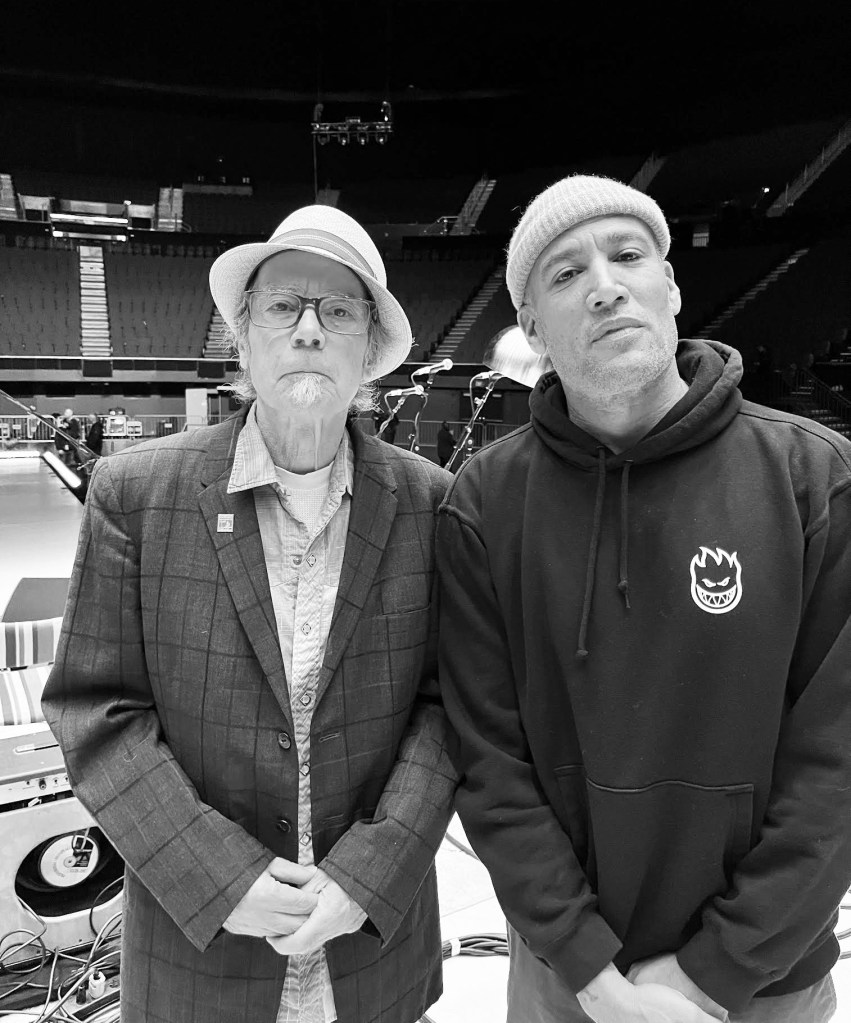

Despite everything going haywire in the world today, to my eyes anyway, the very ‘times’ attired in a bathrobe like me, a pleasant crisp fall day unfolds itself in the clutches of 2023. The sun is combing its molten hair back like a hood, as if dander specks glittering like a visually glowing case of hubris, throwing a blowsy red frock on the modesty of the original Big Bang. As I drink a comically large cup of Columbian coffee, nearly intravenous, the daily news-rag over-confesses of yet another record-breaking heat wave. Along those lines, my good friend and musical inspiration Ben Harper has just appeared in his first acting role, alongside such as Meryl Streep, in a global warming (warning) climate drama entitled, Extrapolations (Apple TV). So everything is tied together too neatly, to the point of exhaustion, leaving you, as if manhandling a knot in a brassy silk tie from the forties, to then untie with hope some things for the better.

Brayer and Harper at The Kia Forum 2023 (photo: Hollace Brayer)

I believe the nature of my humble friendship with Harper is based on our true shared visibility to each other, and not as one might think as one adjoined in musicality. Music is merely the residue of it all. He sees the real me and I see the real him, beyond words and far afield of what might swarm a pack of zithers. That, and the fact that we both come from the vantage of almost debilitating shyness. We both have created, almost out of desperation, a spokesperson to represent us in the finite world. It’s hard to believe that he’s shy by listening to his articulated stories and philosophical healing, but being that way myself I recognize well the difference between the creature and the creation. There are many mediums for expression but there are only two varieties of artists. The one with an introverted standpoint who rises out of the shyness and fights for his or her life against the nature of invisibility in a field of childhood silence. This is the one hiding in the bushes from that truant officer that is the ego. The other type of artist is the extrovert, whose master of ceremony is created wholly by that very same ego. This one fights against the very nature of creativity, putting into question the very need and cause of art. One is not better than the other. Their differences make each other possible. When pulling back they form a picture as a whole, and although the two cannot necessarily see each other, they define each other into our visibility, having a shared need, and that need is each other. But I must confess, if I knew what I was talking about I probably wouldn’t feel the need to talk at all.

Basically, I don’t want to be told, under any melee of surrender, what I’m ultimately here for, made of, or regarding that which regards the absolute. For that would not then allow me to find out for myself, even if forced to pull the strings of puppeted meaning, what I’m here actually attending to, dodging hell-bent through a continent full of cosmic aborigines. Shakespeare thought he was shutting it down. All in hopes that after him we would realize that everything that needed to be said was said, like finding out that Sasquatch, in the distance, always in the distance, turned out to be nothing more than a coffin covered in kudzu. This was all bardic foresight in the hopes that we would then move on to seek the doorway to another plane and await the higher dimensionality of what was once ambiguous human growth. But no, we continue to churn out, even when viewed by a simpleton, scripture to be as no more or less than the perpetual entrails of the brain-dead Penny Dreadful.

We all arrive in the social world as sort of replete in the residue of our boyhood heroes, don’t we? For me it might be, amongst the handful, one boyhood Fontana guitar slinger by the name of Richard Taelour, who came up as he did from the garage-band angsty ranks of our steeltown, now a ghost town with a Nascar track barnacled on its back. Richard’s father could be found making mysterious aircraft in the garage like something deep in the clanging bowels of a Spike Jones song. On the fast track, Taelour was signed by Clive Davis to Arista Records in the eighties,soon after, over childish arguments, the plug was pulled and the cocaine-caliber rewards that dangled like carrots were quickly withdrawn. He walked the streets homeless for a time with an apostle’s gate and guise, only in workboots and a flannel shirt, often parking his ravaged Les Paul at my father’s alcoholic abode. It all came to a head upon his jailbreak-caliber escape from a meth concave in boulder-strewn Lytle Creek, where Chinese immigrants once dynamited for gold at the crack of forgotten centuries, at which time he reinvented himself and his health, barking a convincing song, the gravel in his voice a time capsule of filterless Camels, and with his wife, of hardscrabble parentage, whom he ushered away from a Hell’s Angels lifestyle, all the way to the timbered white flight township of Eugene Oregon, a city where you can go to the town square and drink from a fountain whose waters threatened to heal you in fairytale fashion. Over the years Taelour never lost his magical guitar gifts or grift and he retained a propensity for giving you what you needed as opposed to that of your foolish wants, as his hands spidered in dance across the frets, turning the tumblers of the bank vault that housed emotions yet unnamed. He created with his life a seventy-year-long song that you could almost take a bite out of.

Taelour Les Paul (Photo: Patrick Brayer)

Now 70 somethin’ he settles into all ages at once, playing roadhouses, mentoring teenage jazz violinists, it’s all or nothing, for he’s now all Indian cheekbones, hayloft hair, once but no more butchershop red, with a raked black derby hat that plays a cherry on top of the blues. With the presence of a castle guard, he finesses the daylights out of a Gibson 335, like a tobacco sunburst baby in his arms. A survivor if ever there was one.

Myself, whenever I’m not either in turn a father, or a husband, or delusionally serving as the high holy custodial president, costumed in a serge vestment, as the vaunted head of an ashtray collector’s society. Regardless, I have the lonely mornings to myself in which to scribble away at pen-sought dreamage, while the rest of the household’s participatory membership is off pursuing scholastic endeavors. I don’t worry long over my identity, one that I should, would, or could, as if picking over the remnants of a vaudevillian’s steamer chest, and with no confidence whatsoever, trade in one persona for another. One that in contrast only looks realistic when the mind sees it. Even the perverse author Jean Genet found there to be ill little difference between the jailyard flower and the botanical convict.

I’ve had some luck in the field of musical shenanigans in my time. A lot less than some but a tad more than others. Most recently, Ben Harper titled a meditative instrumental piece on his new record “Thank You Pat Brayer” in tribute to our friendship, The Cox Family (with Alison Krauss) have released one of my songs, a track that had been buried in the dusty vaults of Asylum Records for 18 years. Still, although I am honored, and flattered beyond repair, my place in the scheme of things, in my identity-grappling, is still somewhat opaque. In all honesty, when I try to take it all in, Alison Krauss, Alan Jackson, Michael Hedges, Stuart Duncan, Pat Cloud, Bryan Bowers, I don’t really see music at all as much as I see kindness. What you are reading right now, hand-delivered to your eyes, I find to be, in a conversational style, albeit one-sided, my chosen way of communicating in all honesty. A plethora of factors at play at present might be my turning the ripe age of seventy this coming January, along with being diagnosed with Parkenson’s disease while riding sidesaddle on the pandemic. These all play no small part in my gradual social retreat from the outside world, nor the will of roses. I can’t even for the likes of me imagine what an analyst might tell me, it all just looms up ahead in the distance like a colossal farmer in a tutu.

(The Cox Family: Gone Like the Cotton, alternative cover)

So before we look back into the past drama let us take the advice of Tom Waits in saying, “You can’t live in the present forever” Let’s then now transport ourselves, by way of the nucleus of this story, twenty-five years into the past, which now so neatly and archively houses the year 1998, here-to-for known as the “then”. That is, only if writing were even half as capable of time travel as it’s cracked up to be, and if were true, that the past is truly the mind’s stockyard where we go to hide all of our inquiries, to the tune of cave crickets.

To speak of or for the dead is to coin the phrase ‘dead-end’ all over again. The mystery itself is peppered with landmine-shaped questions. O.K., our lives are a mere splinter in the middle, sandwiched between the past (where did we come from?) and where we go from here, our anachronistic post-life. Oddly we don’t pine when a plant drops its seeds and then passes, and whithers away until it resembles a bible page. Where do we go from here? Your life lives on in that shimmering seed. No different than a petunia. You’re not gone, you’re right in front of your own face. But try to tell the ego that. “As little joy you may suppose in me that I enjoy in just being”. This was a line I was once credited as to saying, although in hindsight I was more than likely mangling a bard’s moment, in mock of Van Gough in his painting away at a chunky skyline. He hardly notices us. I find that of late it’s harder to address death prudently in an all-parts trinity, past, present, future, verses here, there, and everywhere. It’s plain and simple as near-impossible, if not completely as impossible as, say, to dream of being a flute player in a Country and Western band. But the true stylistic nature of writing is to just plug on as if you knew what you were talking about, until hopefully, your story becomes the scuffed flesh of your own stunned amazement. Let us not forget, thespians that we are, that God does punish us with an occasional hate in those where we expect most love.

Carla Coldiron McGill (poetress) at The Roil Academy of Dust, Ontario, CA

Wonderful writing and insight. Thanks for all your posts! So sorry about the diagnosis…I’ve been there before. Hope to look you up if I’m in the same vortex sometime!

LikeLike

Now that was a read ! Life and death music words and flowers! Milk to guitar strings , tons to feathers leaving a want to create a lie or two ones self!

LikeLike